The Hatch Family: Chairmakers at Whielden Gate, Farmers at Woodrow

by Richard Ayres

For nearly one hundred years, three generations of the Hatch family ran a chairmaking business at Whielden Gate, just past the original junction of the lane to Winchmore Hill with the main Amersham-High Wycombe road. In this period, chair workshops (and later small factories) were a feature of many of the villages in the central Chilterns, making use of the abundant local timber.

Overview

The Hatch family chairmaking business began in the mid-1840s when my great-great grandfather David Hatch (1815-1885) set up his workshop near a house called Hollandsdean at Whielden Gate. By its heyday in the early 20th century it employed between 30 and 40 men.

David Hatch’s sons all started their working lives at Hollandsdean, but the business had passed to his third son Joseph by 1881. Joseph (1849-1943) established the company ‘J Hatch and Sons’ with his sons Joseph David, Frederick, Archer and William. Joseph was also a tenant farmer, first in Winchmore Hill, then at two farms in Woodrow. Sometime in the 1930s he passed the chair company to his sons Joseph David and Frederick; the latter died in 1938.

My grandfather, Joseph David (1874-1962), ran the company until he sold it to a timber merchant at the start of the Second World War. Like many village chairmaking factories, by the 1930s it faced competition from larger enterprises in High Wycombe. The premises burned down in the early 1950s.

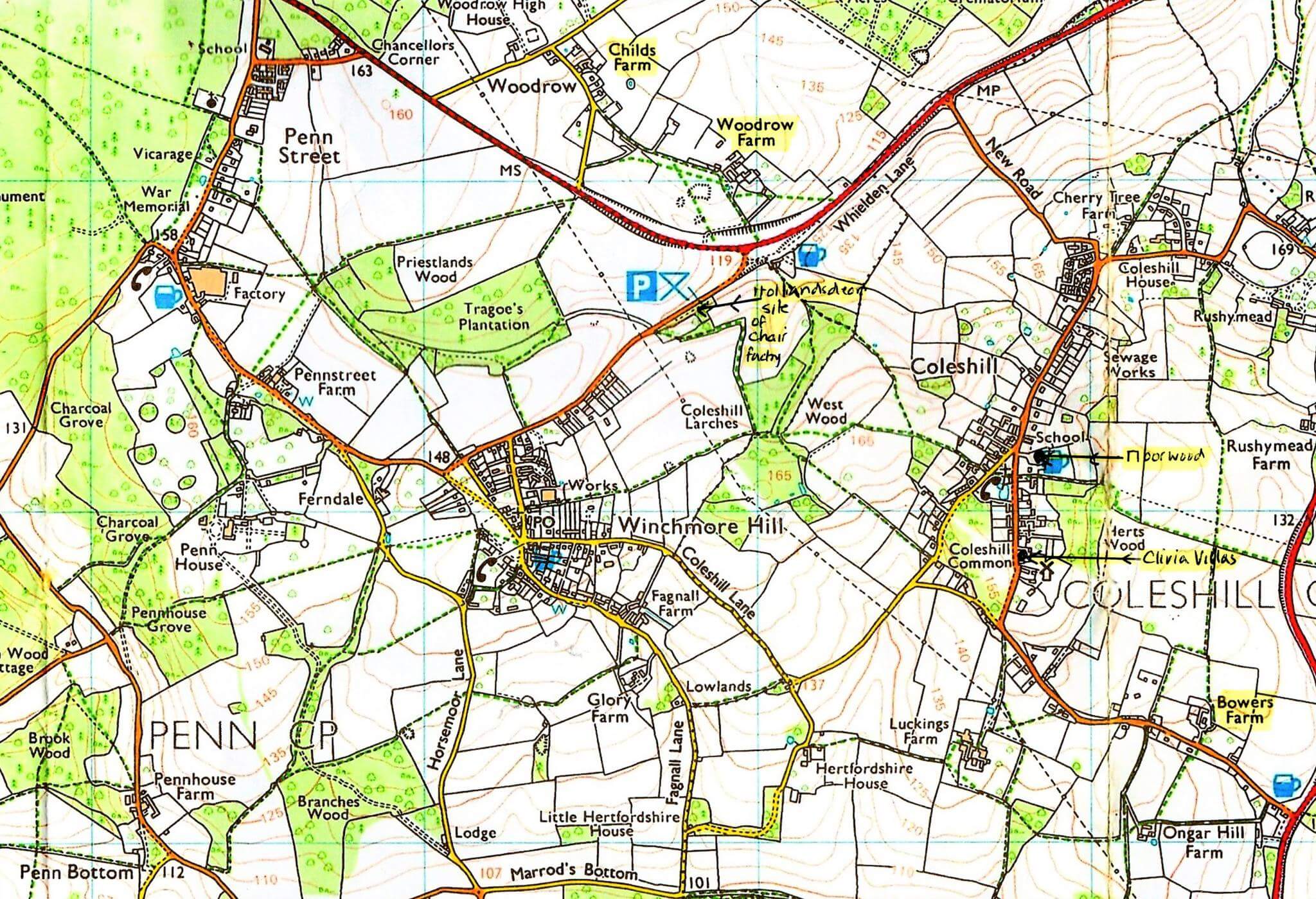

The annotated Ordnance Survey map below may help the reader to locate the various places mentioned in this article.

(Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown Copyright and Database Right 2021 Licence No. 100044050)

David Hatch 1815-1885

David Hatch was the grandson of William Hatch of Bowers Farm, Coleshill (1743-1820) and the son of Daniel Hatch, saddler of Amersham.

In 1841 David was a 25-year-old chairmaker living with his wife Elizabeth and their 3-year-old daughter in the hamlet of Woodrow. The listing of the census indicates they were probably living in Cherry Lane near ‘New Lodge’.

By the time of the 1851 census David had moved to the house called ‘Hollandsdean’ near Whielden Gate, where he was described as a ‘chair manufacturer’. It is possible that his rise in status from chairmaker to chair manufacturer resulted from his being left £100 by his uncle who died around 1845.

Hollandsdean

A study by John Chenevix-Trench of 17th-century buildings in and around Coleshill identifies a dwelling called ‘Hollandsdean’ and another nearby called ‘Henry Child’s Cottage’ standing on the south-east side of Whielden Lane a few hundred yards to the south-west of ‘Cokes’, the building which became the Queens Head pub. It is not certain that Hollandsdean was the house into which David moved, but my aunt Elsie Stubbings could clearly remember the remains of an old house in the factory yard at the time of her childhood in the early 1900s.

The factory came to occupy the area to the left of the lane going towards Winchmore Hill. The land on which it stood was occupied on a ‘copyhold’ basis (a traditional form of tenancy where the owner is a wealthy landowner) from the Shardeloes estate, owned by the Tyrwhitt-Drakes, squires of Amersham. Between the factory and the Queens Head, on the opposite side of the road, stood a toll house built around 1879 when the road from Amersham to High Wycombe was turnpiked.

The Hatch chair factory. The photograph was taken in about 1910. (Stuart King Archive)

David is recorded as a ‘chair manufacturer’ at Whielden Lane in the censuses of 1851, 1861 and 1871. His sons John, George, Joseph and William are all described as chairmakers in the 1871 census, all living with, and presumably working alongside, their father.

As the 19th century progressed, there was a growing number of employees in the chair workshops, and a resulting decline in the number of chair bodgers working in the woods. In the 1861 census David Hatch had three apprentices at Whielden Gate, but there is no record of any specialisation of labour, and there is no indication of specialisms in subsequent censuses.

It would seem that the chair factory had passed to David’s son by the time of the 1881 census. David had moved to live with his daughter and son-in-law George Wilkins in The Row, Winchmore Hill. I do not know why the factory passed to David’s third son Joseph rather than to his two elder brothers. David died in 1885. There is no record of any probate being granted: either his assets were too small, or he had passed them all on before his death.

Joseph Hatch 1849-1943

Joseph was probably born in Hollandsdean, Whielden Gate, as the 1851 census lists him there as a one-year-old. He is listed as a ‘scholar’ in 1861. This was some 15 years before the introduction of universal elementary education; it seems that the term ‘scholar’ was often used to indicate an apprentice. In 1871 he was working at Whielden Gate alongside his father David.

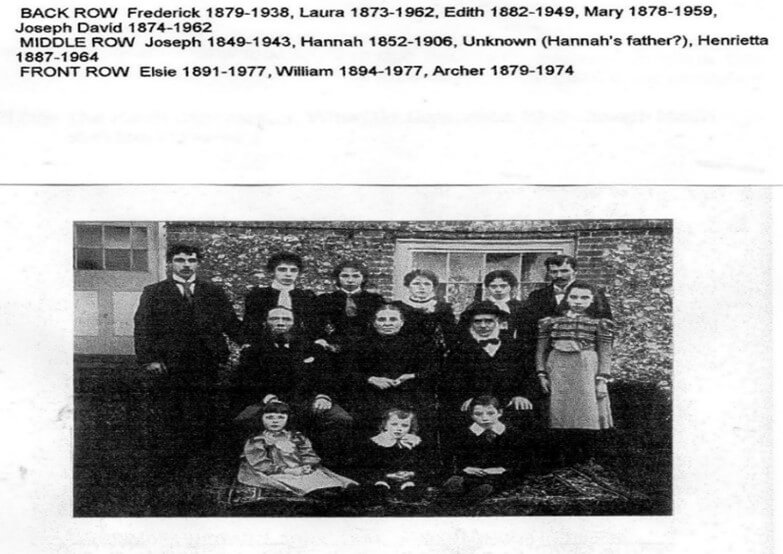

By 1881 he had married Hannah Taylor from Chalfont St. Giles, and had evidently taken over the running of the chair factory from his father, as he was living there with Hannah and five children – William aged 9, Laura 8, Joseph David 6, Mary Ann 4, and Frederick 1. (They went on to have seven more children – Elizabeth, Edith, Edward, Henrietta, Archie, Elsie and a second William, the first William having died aged 14. The photograph below of the family was taken in 1896 after they had moved to Woodrow Farm. The elderly man in the photograph is assumed to be Hannah’s father.

Hatch family 1896, taken outside Woodrow Farm

Towards the end of the 19th century, industrialisation of chair production began with the introduction of machine tools. In the early 1900s a plank-cutting machine was installed at the Whielden Gate factory. (Local resident Sid Wingrove’s memoir says ‘The first plank cutting machine I remember was installed at G. (sic) Hatch’s factory in Amersham Lane. It was called a jig-saw and was driven by a petrol engine. So that was the end of the old saw pit.’)

After 1881 Joseph and his family moved to Winchmore Hill, on the opposite side of the common to The Plough inn. In the 1891 census Joseph was listed there as a farmer and chairmaker: he was farming as a tenant of Earl Howe of Penn. Sometime after 1891 the family moved to Woodrow Farm, part of the Shardeloes estate, but Joseph was still farming Earl Howe’s land in Winchmore Hill and still running the factory.

Joseph was listed at Woodrow Farm in the 1903 and 1907 Kelly’s Directories, but in the 1920 directory he is listed as a farmer at Childs Farm, Woodrow, also part of the Shardeloes Estate. By the 1920s his business was known as ‘J. Hatch and Sons’, as Joseph David, Frederick, Arthur and William were all involved in it to a greater or lesser degree.

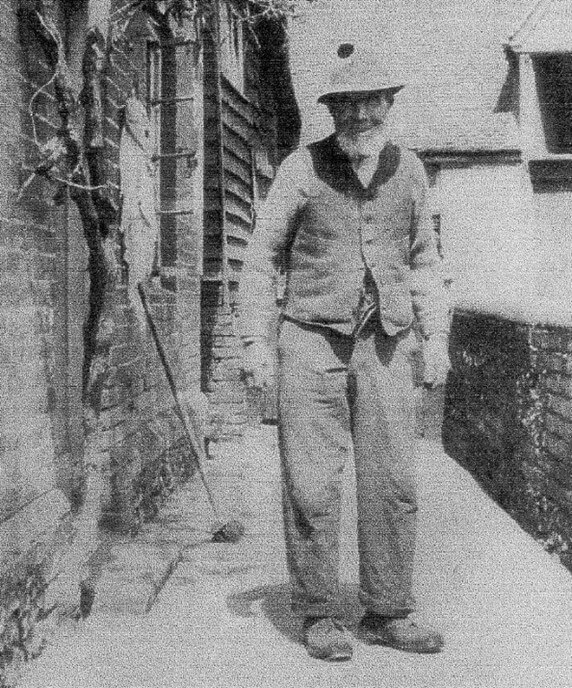

The photograph below, taken in the late 1930s, shows Joseph as an old man standing outside Childs Farm.

Joseph Hatch at Childs Farm

The chairmaking business evidently prospered. Joseph began to accumulate property, buying cottages and having new houses built in Winchmore Hill, and later owning property in Hazlemere. He purchased Nos. 1 to 7 in The Row, Winchmore Hill, as early as 1887. He continued to live at Childs Farm until about 1938, when he moved to ‘Leylands’, Holmer Green Road, Hazlemere, to live with his unmarried daughter Henrietta who looked after him in his declining years, his wife Hannah having died in 1906.

At some point in the 1930s Joseph must have passed the chairmaking business to his two eldest sons. Joseph David and Frederick. This assumption is based on the fact that Joseph David was not mentioned in his will (Frederick had died in 1938) whereas William and Archer were.

Joseph Hatch – a famous local character

As late as 2005 Joseph was still remembered by a few old locals. He was famous for driving a horse and trap, with his white beard flowing in the breeze. My mother recalled that his beard was once caught in a lathe and a chunk of his skin was torn off. John Deacon remembered how he used to join with other children in hiding in the hedgerows and throwing stones at Joseph as he drove to Wycombe – Joseph used to lash at out them with his whip.

My mother’s maternal grandmother Emma Pursey (wife of Thomas Pursey licensee of The Plough in Winchmore Hill), told my mother she had once heard Joseph’s workers discussing him in the bar – ‘That Joe Hatch ‘e might be ‘ard but ‘e be a just b*****r.’ Apparently in 1913 there had been a lock-out by chair manufacturers in High Wycombe when their workers demanded higher wages: a deputation was sent to Joseph to persuade him to join the lock-out, but he refused.

Another story told by my mother was when Joseph was suffering from toothache and he asked one of his workers to knock out the offending tooth using a mallet and chair-spindle: when the man refused, Joseph threatened to sack him.

Although stern, he was very fond of his daughter-in-law Kate (nee Pursey) and used to bring her breakfast in bed when she stayed at his farm, much to her mother Emma’s amazement. My mother remembered him dressing like a tramp (this is borne out by the photograph taken of him standing outside Childs Farm) and being very tight with his money.

Although Joseph moved to live with his daughter Henrietta in 1938, he died on 20 November 1943 at the home of his son Archer at ‘The Cottage’ in Woodrow. (The doctor who certified his death went straight to Winchmore Hill to deliver Maureen Marshall, great-grand-daughter of Joseph’s brother William.) Joseph is buried in Penn Street churchyard, and memorials (and perhaps the ashes) of numerous other Hatch family members are located around his headstone.

Joseph’s Will

On Joseph’s death, administration was granted to his son Archer (Henrietta having ‘renounced’ probate and execution). The gross value of the estate was £9,895 (equivalent to about £470,000 today) of which £5,332 was property. He left ‘freehold land at Winchmore Hill together with the 14 messuages or dwelling houses thereon’ to his son William, and a payment of £3 a week to William’s wife Ethel should be made ‘for as long as she remains a widow’.

He left the dwelling house ‘Leylands’ in Hazlemere with all its land and premises, together with furniture and fittings to his daughter Henrietta ‘for as long as she remains unmarried’. After her death or marriage, the property was to pass to his son Archer. No mention is made in the will to any of his daughters except Henrietta. He had already helped the husbands of his other daughters set up various businesses. No mention is made of his son Joseph David, who had already inherited the chair factory. Frederick had died in 1938.

Joseph David Hatch (1874-1962), and his brothers Frederick, Archer and William

Joseph David, (known to all as ‘Joe’) was presumably born at Hollandsdean: in the 1881 census he was living with his parents in Whielden Lane, the parish of his birth given as Amersham. In the 1891 census he was in Winchmore Hill with his parents, aged 16 and described as ‘farmers son, neither employer nor employed’. He had left Woodrow school at the age of 11, and then accompanied one of his father’s workers delivering chairs by horse and cart to London, and also as far as the south coast and Manchester.

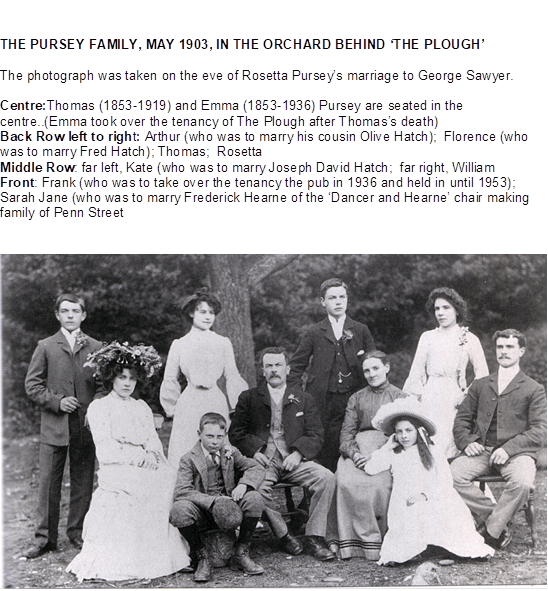

He moved with his parents and the rest of the family to Woodrow Farm in the 1890s, and in the photograph (see above) he is standing on the far right of the back row. In 1903 Joe married Kate Pursey (born 1875), daughter of Thomas Pursey, the licensee of The Plough in Winchmore Hill. Three generations of Purseys were licensees of the pub, starting with Thomas’ father George in the 1870s, followed by Thomas (and then his wife Emma after his death), then Thomas’ youngest son Frank who held the tenancy until 1961. Thomas was also a chairmaker, as were many of the Pursey family. Many members of the Hatch and Pursey families intermarried over three generations, and to examine the complexity of this would require a separate article!

In the photograph below, taken in 1903, Kate is sitting on the left of the middle row. At the time she was in service in London, which probably accounts for her fashionable dress. According to Kate (my grandmother) the photo was taken at the rear of The Plough, but not where the present car park is located, as this area housed the chairmaking workshop.

The Pursey Family

In the early years of the 20th century the Hatch chair factory probably reached its peak of production. During this period Joe was jointly running the factory with his father and his brothers. He was still taking chairs to London by horse and cart in my mother’s memory (1910s). At that time both sides of the Wycombe Road and Whielden Lane were used to store timber harvested from the beechwoods. Some 30 to 40 men worked at the factory in its heyday, and in addition the company employed outworkers living in the surrounding villages from as far away as Speen; wood and cane were delivered to their cottages for turning and caning. Local people used to visit the factory to collect woodcuttings, firewood and sawdust. The premises were lit by oil lamps, which must have been a considerable fire risk.

The early years of Joe’s marriage to Kate were spent in ‘Hope Cottage’ (still thus named) near Amersham station. He moved here because his role at the time was to market the company’s chairs in London, and he travelled there by train. Hope Cottage had only recently been built opposite The Railway Hotel (later The Iron Horse, demolished in 2004). It was in Hope Cottage that his daughters Elsie and Ethel were born, in 1904 and 1906 respectively. Joe was in the Buckinghamshire Yeomanry, and the photograph below, taken in 1904, shows him in uniform on horseback outside Hope Cottage. As a member of the Yeomanry he was present on Coombe Hill at the unveiling of the monument to those who died in the Boer War.

Joe Hatch, Yeomanry

Sometime between 1907 and 1911 the family moved to Coleshill, to live in one of a pair of Victorian cottages near the windmill called ‘Clivia Villas’ (now converted to one dwelling called ‘Hill Cottage’ after a period when it was called ‘Clivia’). Here Joe and Kate had a son Ronald, who died in early childhood. His fourth child Edith, my mother, was born here in 1913.

The chairmaking business prospered, and Joe purchased two cottages opposite Coleshill church and next to The Red Lion. He converted them into a single dwelling which he named ‘Moorwood’ (now ‘Morewood’) and the family had moved into it by 1926.

The photograph below was taken in the early 1920s before they moved to ‘Moorwood’ and shows Joe on his motorbike and his family in the sidecar.

Hatch family motorbike, early 1920s

Later, Joe became the second person in the village to own a car, the first being Mr Forbes who lived at the Manor House near the Beaconsfield Road.

My mother had many memories of her childhood and adolescence in Coleshill. She could remember running from ‘Moorwood’ through the fields on the path that led down to the Queens Head and then to the nearby chair factory, and the adders that used to sleep in the piles of sawdust in the factory yard. Joe worked a 12-hour day at the factory, 7am to 7pm, and in the summer he used to work in the garden after arriving home; the family were self-sufficient in vegetables. In any case his wife Kate never had to go shopping for food as provisions were delivered by van, though occasionally she visited ‘Freddy Fuller’s’ emporium in Whielden Street, Amersham, and specialist shopping was done in High Wycombe.

The photo below is of ‘Moorwood’ with Joe’s daughter Ethel standing outside. The photo was taken in the 1930s, and the exterior of the house has changed little since that time.

‘Moorwood’, Coleshill, in the 1930s, with Ethel Hatch

In 1936 Joe and Kate and their remaining unmarried daughter Edith moved to a house at the bottom of First Avenue, Amersham, and Joe named the house ‘Moorwood’ after the house in Coleshill. The move was prompted by the fact that Edith had started work in the office of builder Robin Brazil in Amersham and Joe did not want her to walk there all the way from Coleshill, (though she had walked from Coleshill to Dr Challoner’s Grammar School in Amersham-on-the-Hill when she was a teenager.)

Foreign timber imports began to reduce the need for Chiltern beechwood, and towards the end of the 1930s the small rural chair factories also began to decline when faced with competition from the larger enterprises, mainly in High Wycombe. With the death of his brother Fred, Joe was left to manage and market the firm singlehandedly. He wound up the company and sold the Whielden Lane premises to the Dunmore brothers, timber merchants, at the start of the Second World War. The buildings (which I can remember as a child) were destroyed by fire in the early 1950s. The site was turned into a picnic area in the 1970s or 1980s, but by 2019 it was no longer managed and is now totally overgrown with trees.

Joe is remembered as a gentle, quietly spoken musical man who was rather ‘straight-laced’. Kate took after her mother Emma Pursey; she had a fairly bawdy sense of humour and quite a sharp tongue. She also had an inexhaustible supply of childhood memories which she delighted in recounting to her grandchildren.

Joe died at his home in Amersham in 1962, and Kate at a nursing home in Beaconsfield in 1969. Their ashes were interred in the grave of their two-year-old son Ronald in Penn Street churchyard, but no headstone was ever erected. The church records of burial sites were inadvertently destroyed, so the location of the grave will remain a mystery.

Frederick Hatch 1879-1938

Unlike his elder brother Joe, Frederick was not described as a ‘farmer’s son’ in the 1881 census, but he did join the family chairmaking business. He married Florence Pursey, sister of Kate, in 1907. After their marriage, they moved to ‘Ivy Cottage’ in Coleshill, and in the 1920s Fred moved to a large house (‘Glebefield’, built by Florence’s brother Arthur Pursey) to the north of the church on the east side of the road. This house was demolished in the early 21st century.

Fred’s main role in the chairmaking business was to do most of the office work, but he was also responsible for spraying the timber, possibly with preservative. This was done in a confined space, and to this Florence attributed his early death from cancer in 1938. He is buried in Coleshill churchyard.

Archer Hatch 1889-1974

Archer, who according to the records of Woodrow school seemed to be prone to ill-health, was the only one of Joseph Hatch’s children to attend secondary school. He left Woodrow school on 22 January 1901 and ‘proceeded to the Grammar School’. This would have been the old Dr Challoner’s premises in Amersham market square, and William would presumably have still been a pupil when the school moved to its new buildings in Amersham-on-the-Hill in 1906.

Archer served in the First World War, joining the army in 1915, then leaving it, probably as the result of an injury, but then re-joined it in 1918. His occupation when he first joined the army was given as ‘bailiff’. Although he worked in the factory, the precise business relationship with his father is not clear. In Joseph’s will he is described as a ‘wood sawyer’, but he was known to also have worked on his father’s farm.

He benefited from his father’s will after the death of his sister Henrietta, inheriting ‘Leylands’ (or whichever house Henrietta moved to after her father’s death) from her as well as whatever remained from Joseph’s legacy to her. Arthur lived in ‘The Cottage’, Woodrow (the house still stands and is still thus named) and it was here that his father died.

William Hatch 1894-1977

William was Joseph Hatch’s youngest son. He served in the trenches in the First World War.

He worked for his father, seemingly as an employee rather than as a partner: towards the end of Joseph’s life he was being paid £3 a week, £1 less than some of the men. At one time he lived in the old toll house (demolished in 1925 for road widening) which was situated on the opposite side of Whielden Lane to the chair factory.

In the photograph below was taken in about 1900. Note The Queens Head pub on the right.

Toll house, with The Queen’s Head in the background (Amersham Museum)

While living in the toll house, William was the first to arrive at the factory to open it up and the last to leave after locking up. In 1926 or 1927 he and his family moved to Woodrow where they stayed until moving to ‘Kingsbury’ near the Lord Nelson pub in Winchmore Hill. (The Lord Nelson was situated at the end of Whielden Lane at its junction with the common. It closed in the late 1950s and was demolished in 1960 to be replaced by a row of houses called ‘Nelson’s Close’.)

After his father moved to Hazlemere to live with Henrietta, William used to cycle over every Sunday to shave his top lip. William was remembered as a gentle lovable man by his children and his nieces and nephews.

William inherited 14 houses in Winchmore Hill from his father: they were assigned to him in 1944. The properties, particularly the seven in The Row on The Hill, were in a bad state of repair, and after the war the rents were frozen at five shillings a week. The council insisted that repairs be carried out. Re-tiling and renovating the outsides used up most of William’s £500 cash inheritance and there was no spare money to effect internal repairs. William sold the cottages to Arthur Clarke of Chesham, who it is thought sold them on to the sitting tenants. At the time of his death William owned ‘Kingsbury’ and one other property in Winchmore Hill.

He continued to work at what had become a timber factory at Whielden Gate after his brother sold it. After it was destroyed by fire he went to work at Dancer and Hearne’s chair factory in Penn Street until his retirement. His father must have been turning in his grave – Dancer and Hearne were arch rivals of the Hatchs.

William died in 1977, one year after his wife Ethel.

J Hatch and Sons – advertising material

When I was a child, my grandfather Joe Hatch had in his house in Amersham a vast collection of blotting papers on the back of each was an advertisement for the chairmaking business. I was allowed to scribble all over them. I learned later from my mother that this advertising material was rarely used because of the misspelling of ‘Whielden’. A few un-scribbled-on blotting papers still remain with me.

Sources

- Buckinghamshire Nonconformist Records

- Dr Williams’ Nonconformist Index

- Posse Comitatus for Buckinghamshire

- Census returns for 1841, 1851, 1861, 1871, 1881, 1891, 1901

- 1815 Enclosure Award map of Amersham

- Kelly’s and Pigot’s directories for Amersham

- Will of Joseph Hatch

- Woodrow School logbook

- ‘Fields and Farms in a Hilltop Village’ by John Chenevix-Trench (Records of Bucks 1977)

- ‘Life in Winchmore Hill in the early 20th Century’ by Stuart King, this being the transcription of the recorded recollections of Sid Wingrove, resident of Winchmore Hill in the early 20th century

- ‘Houses of Coleshill: the Social Anatomy of a 17th Century Village’ by John Chenevix-Trench (Records of Bucks 1983)

- ‘The Buckinghamshire Landscape’ by Michael Reed (Hodder and Stoughton 1979)

- ‘The Chilterns’ by Leslie Hepple and Alison Doggett (Phillimore 1994)

- ‘A History of Coleshill’ by Julian Hunt (RJL Smith & Associates 2009, from which the photographs of the Hatch chair factory and the old toll house have been copied.

- All other photographs are from the family archives.

Thanks are due to –

- · The late John Chenevix-Trench of Coleshill, local historian, whom I was honoured to meet

- Stuart King of Holmer Green, chairmaking historian, in particular for the tape recording he loaned me of my aunt Elsie Stubbings, nee Hatch, talking in the 1970s about the Hatch and Pursey chairmaking businesses

- Monica Mullins, former Hon. Curator of Amersham Museum

- John Deacon, formerly of Woodrow

- John and George (‘Jack’) Wilkins

- Ken Sears of Winchmore Hill

- Second cousins Maureen Seymour, Enid Leonard and Wendy Calder, third cousin Eileen Thompson, third cousin once removed Albert Pursey, fourth cousin once removed Gillian Figures

- My late mother Edith Ayres nee Hatch

If you would like to know more about Winchmore Hill and the Pursey family at The Plough pub, see Jane Barker’s article published here on 17 December 2020.

Related news

Bluebells: the sign of spring in the Chilterns

Bluebells flower in abundance in ancient woodland in early spring and are found throughout the Chilterns.

The history of Chilterns chalk figures

Learn about the history behind some of the chalk figures cut into hills across the Chilterns.

‘Major victory’ for Beacons of the Past

The hillfort at Cholesbury Camp has been removed from Historic England’s Heritage at Risk register after successful restoration and maintenance work.