Landscape character

The chalk that lies beneath your feet in the Chilterns supports a set of unique features and landscape character types.

The beautiful rolling hills, wooded valleys and steep chalk escarpments of the Chilterns National Landscape have been shaped by both natural means – geology, weather and animals – and by humans over many centuries through farming, extraction, industrialisation and management.

Discover the timeline of the Chilterns

There has been a rich and varied geology and history in the Chilterns – from prehistoric times, when warm, shallow seas laid down the distinctive chalk of the area, through Bronze Age settlements, Victorian industry, right up to today’s working landscape.

Landscape Character Assessment

Landscape Character Assessment (LCA) is a tool that can help us to understand what the landscape is like today, how it has come about and how it may change in the future. LCAs identify and explain the unique combination of features that make landscapes distinctive by mapping and describing character types and areas.

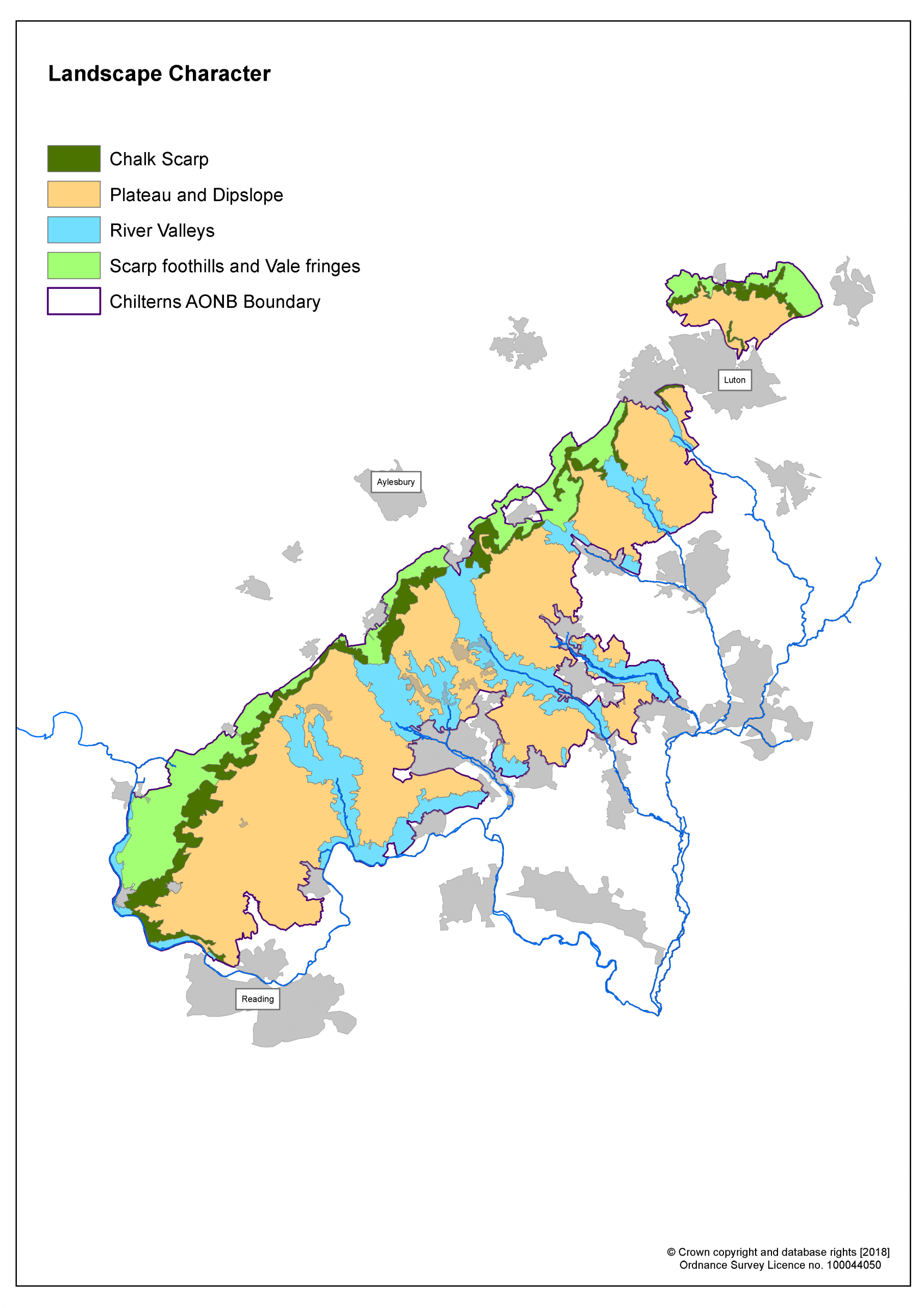

There is no single LCA for the Chilterns National Landscape. The area is covered by several county- and district-based LCAs that have been undertaken using similar (but not identical) methods. These assessments show that the Chilterns has four broad landscape types: scarp foothills and vale fringes; chalk scarp; plateau and dipslope; and river valleys.

The landscape types of the Chilterns National Landscape

Scarp foothills and vale fringes

The scarp foothills and vale fringes consist of the gently undulating chalk slopes with chalk springs between the base of the scarp and the clay vale to the west. In the north of the Chilterns, this landscape is just a narrow band of a few fields, but further south, near the Thames, the area is much wider. There is a striking contrast in colours, textures and form between the vale and the scarp as it rises to the east.

Variation in vegetation and land use within the scarp foothills and vale fringes creates subtle changes in landscape character. Most of the area is under intensive agricultural use, with large, ploughed fields and flinty soils. Field patterns date from the 17th century when the medieval open fields were divided up through parliamentary enclosure. Farming is mainly arable, with relatively few hedgerows or other semi-natural habitats. There is little woodland cover across much of the area.

This area has evidence of settlement dating back to prehistoric times. The light soils, fresh springs and access to the Icknield Way would have made it an attractive place to set up home. Eventually, some of those settlements expanded to become the market towns we know today, such as Tring and Princes Risborough.

- Visit Chinnor Woods, North Stoke Common or Pulpit Hill in the scarp foothills and vale fringes, or search our interactive map for more great days out.

Chalk scarp

The ‘spine’ of the Chilterns is the chalk scarp that runs roughly north-east to south-west along the western side of the National Landscape. A spectacular ridge rises high above the vale to the west and dominates views over a wide area. Combes and prominent hills form a deeply convoluted and steep edge that supports a mosaic of chalk grassland, woodland, scrub and parkland. Where arterial valleys cut through the chalk, great ‘amphitheatres’ have been formed, such as those at Tring and Wendover.

The chalk scarp contains a high concentration of prehistoric monuments, such as burial mounds and hillforts, revealing its ritual and functional importance over the millennia. Figures cut into the chalk, such as the cross at Whiteleaf Hill and the lion at Whipsnade Zoo, and structures on the summit, such as the Coombe Hill monument, are prominent landmarks. The Icknield Way – a route that has been in use since prehistoric times – follows the scarp, while other roads tend to run along the base of it.

There is little settlement on the scarp itself, but it is a popular place for visitors. The Ridgeway National Trail follows the scarp, offering exhilarating views like those at Ivinghoe Beacon and Dunstable Downs. There are extensive areas of chalk grassland on the open scarp, filled with herbs and grasses, and supporting many different insects, mammals and birds. Traditionally, much of the scarp would have been grazed by sheep, cattle, horses and donkeys – all keeping the scrub at bay – but this method of farming has been in dramatic decline since the 20th century. Natural succession has caused an increase in scrub and secondary woodland growth, linking established areas of deciduous woodland and creating a cloak of seasonally changing colours across the scarp slopes.

- The Icknield Way – a route that has been in use since prehistoric times – largely follows the base of the scarp. Some of the route has been lost to history, but the parts that are still in place are often distinguished as ‘Upper’ and ‘Lower’, probably following old seasonal routes as higher ground would have been more passable in winter.

Plateau and dipslope

A large proportion of the National Landscape is covered by plateau and dipslope as the land gradually falls away to the east and Greater London. Though less visibly striking than the scarp, it forms a key part of the classic Chilterns landscape. Areas of the plateau are dissected by long, narrow and often dry valleys, and views are broken by extensive woodlands. Here, a deep sense of history and tranquillity can be found as much of the landscape has remained unchanged since medieval times.

Settlements on higher ground are often found along the edges of commons – areas where a specific group of people hold rights to use privately owned land for grazing, fishing and materials. Villages developed quickly and informally during medieval times, when commons and greens were far more extensive. Today, some commons are still grazed, but most are used for recreation. Many commons in the Chilterns are wooded or former wood pasture (where animals graze under trees), with areas of heathland, acid grassland, ponds and other open habitats.

The shallower slopes of the plateau and dipslope are in arable cultivation. It is an ancient area of farming, with the first field systems being set out around 2,000 BCE. This landscape also contains most of the Chilterns’ surviving pre-18th century field patterns, as well as a network of ancient lanes, hedgerows and trees. Woodlands are generally found in the areas that are most difficult to plough, such as the heavy clay soils of the plateau and ridge tops. For centuries, the woods of the Chilterns were managed to produce timber for industry; in fact, much of the famous Chilterns’ beech woods were planted in the 18th century to provide materials for furniture making.

The Chilterns contain a relatively high proportion of land within country estates, with some of the largest found in the central part of the National Landscape, such as at Ashridge. Estate landscapes include parkland, farmland, woodland, wood pasture, lakes, country houses, villages and estate buildings. Some have origins as medieval deer parks, while others were laid out in later times with examples of work by well-known landscape designers, such as Capability Brown and Humphrey Repton.

- Visit Ashridge Estate, Berkhamsted and Northchurch Common, or Nettlebed Common in the plateau and dipslope. Search our interactive map for more great days out.

River valleys

The Chilterns contains a series of larger river valleys that cut through the scarp and dipslope. They can be dramatic, particularly where the rivers have cut through the chalk escarpment to create ‘wind gaps’, such as at Tring and Wendover. Often asymmetrical in shape, some valley sides contain spurs and coombes, while others are smoother in profile. They often have an enclosed and secretive quality, and contain internationally rare, aquifer-fed chalk streams. Some sections of these streams, known as ‘winterbournes’ only flow when the water table is high after the winter rains.

As natural corridors through the Chilterns, there is a long history of settlement and travel in the valleys. From ancient drovers’ routes and canals, to modern day road and rail links, there is a wealth of infrastructure. Several large, historic houses preside over estates and parkland in the valleys, and settlements are associated with the water supply, woodland industry, farming, trade and transport links to London. The valley floors contain smaller, irregular field patterns, which become larger and more regular areas of pasture further up the valley sides.

There are three distinct types of river valley in the Chilterns:

- Arterial river valleys – these parallel valleys run north-west to south-east through the Chilterns, cutting through the scarp. They contain the Wye, Misbourne, Bulbourne, Gade and Ver rivers, and have been used as transport corridors for millennia. They carry Roman roads, the Grand Union Canal, turnpike roads and railway lines through the Chilterns.

- The Thames river valley – located at the southern edge of the National Landscape, this area comprises the broad sides and floor of the Thames Valley. As the climate warmed after the last ice age, the River Thames changed its course, eroding the chalk to create the significant landmark of the Goring Gap. The settlements of Goring, Whitchurch-on-Thames and Mapledurham developed at crossing points (bridges or ferry landings) over the Thames.

- Non-arterial river valleys – the non-arterial Chess Valley has a very distinctive and pastoral character as the clear chalk stream of the River Chess meanders through species-rich water meadows, past networks of hedgerows, woodlands and small parklands.

Visit Goring and Streatley for a day out by the river, or walk the Grand Union Canal through Tring and beyond. Search our interactive map for more great days out.

Related news

Bluebells: the sign of spring in the Chilterns

Bluebells flower in abundance in ancient woodland in early spring and are found throughout the Chilterns.

Calling all artists: new national arts programme

We are seeking writers and artists to take part in Nature Calling – a new national arts programme.

Revitalising the Hamble Brook

For the first time in more than 140 years, the Hamble Brook has a new wetland site.