The story of Thomas Gilbert, Lace Dealer of Wycombe

by Susan Holmes

Another fascinating tale of Woodlander’s Lives and Landscapes, revealed by volunteer Susan Holmes and shared with us in this short story. Grab a cup of tea/ coffee/ hot chocolate and dive into Thomas’ world, beginning in 1825…

We know quite a lot about the history of lacemaking in Buckinghamshire, but less is known about the lives of the lace dealers who bought and sold the lace and specified the designs. Using information from the UK census 1841 to 1911, newspaper articles and trade directories, I have been able to trace the life of Thomas Gilbert (1825–1904) who was a pre-eminent lace dealer of the Wycombe area in the Victorian era. His working life spanned the height and fall of the lacemaking business in the area, and he is said to have originated the connected industry of beadwork locally. We are still discovering more about how these businesses worked. I have a personal interest – my 3x great-grandmother Jane Rogers was a grocer and lace dealer at Askett near Princes Risborough from the 1850s to the 1870s and she may have been an agent for Thomas Gilbert.

Thomas Gilbert’s early life and family

Thomas Gilbert was born 1825 in Princes Risborough, the son of James and Frances Gilbert who ran the George Inn in the High Street. Around 1840, when he was about 14, Thomas was apprenticed to Daniel Hearn, lace dealer of Wycombe, which lies 8 miles to the south. Thomas Gilbert’s family were neither well off nor well-connected but they were quite enterprising – by 1851 his parents had moved to London and ran a beer shop in Paddington; they then moved in with his sister Frances who ran a cheesemonger’s in St John’s Wood, London, with which Thomas was also involved. His brother William was a miller in Princes Risborough but moved to South Australia after 1861 (aged around 40) where he became a Member of Parliament for 26 years. In the 1860s, at the height of Thomas’ success, his brother John (originally a tea-dealer’s shopman in Lambeth) ran a draper’s shop in Chinnor, but by 1871 John was back in Lambeth.

Lace terms and definitions

Pillow lace (also known as bobbin lace) – a lace textile made by braiding and twisting lengths of thread wound on bobbins to manage them. It is held in place with pins set in a lace pillow, the placement of the pins usually determined by a pattern or pricking pinned on the pillow. Sometimes it is called bone lace, because early bobbins were made of bone or ivory.

Yak lace – coarse bobbin lace typically made from wool, which was cheaper and faster to make, often used on mourning garments.

Lace card-maker, lace pattern-maker – the dealers supplied the lacemakers with patterns to follow for the latest fashions. These were marked out on cards by pattern makers.

Lace man – a male dealer in lace, who sold or supplied raw materials to home-based workers, then sold the lace goods they made.

Commercial traveller – a term used for well over a century for men who travelled selling the product of a business or factory. It was paid by way of a small basic salary and some commission on sales.

Hawker – a travelling pedlar who sold wares on the street.

Lace dealing in the Wycombe area 1830s to 1850s

Lace was made by predominantly female lacemakers in the Chilterns villages and sold to lace dealers who then sold it on to wholesalers and distributors, often in London, or in their own shops. The lace dealers supplied the lacemakers with the materials and patterns to make the lace and bought their products. They either dealt with the lacemakers directly, travelling around to visit them, or sometimes through the local grocers/drapers in the villages, to which lacemaking schools were sometimes attached.

View of some 15 girls, who are holding lacemaking materials, and 4 women, outside a building, probably a lace school, Stokenchurch, c.1860. Courtesy of SWOP/Bucks Free Press

Hearn and Veary

In the 1830s, Daniel Hearn (1788–1851) of Wycombe built up the local lacemaking business; from at least 1823 he ran a large drapery and grocery shop in Easton Street, Wycombe in partnership with Joseph Veary who came from an established family of grocers and tallow-chandlers. In the early 1830s they were already selling lace and they sold lace into London with a partner William Kendle of 9 Cheapside, a British and foreign lace dealer and lace manufacturer. Robson’s Street Directory of London, 1842 lists:

9 Cheapside: Kendle W, lace manufacturer Hearne and Veary, lace mnfrs

They advertised a wide variety of goods:

“a splendid collection of India, Norwich and Edinburgh Shawls, of new and novel designs; a large assortment of Gros de Naples, in every colour; a curious and rich assortment of gauze and other ribbons, French blond laces, black lace veils, leisse gauzes of various colours; also a large assortment of muffs, boas, mantrillos, tippets; silk cloaks of the newest patterns; French and English merinos, Pelisse cloths; Welch and Lancashire flannels, blankets, counterpanes, quilts, carpeting, rugs etc.”

(Bucks Gazette, Saturday 06 November 1830)

“Broad silks, Silk Norwich, Scotch and Thibit shawls, French and English blands, gauze, lutestring and other ribbons; plain and printed ginghams; French cambrics; plain muslins of every description; silk and fancy cotton hose; India bandanas; French and English gauze and crape shawls; handkerchiefs, scarfs, bobbin and quilling nets.”

(Bucks Gazette, Saturday 30 April 1831)

After 1843, Hearn & Veary opened a new shop at Buckingham House, 36 High Street, known locally as “Bobbin Castle”. It was where WHSmith is now – they bought the land for £1700. It is described here: “Nos. 38, 37 and 36 Mr. Sherriff’s and Buckingham House were formerly the ‘Catherine Wheel’ the oldest house in Wycombe and perhaps the most beautiful […] Buckingham house was built by Mr. Daniel Hearn on the site and it was also a very handsome modern structure designed by a Regent Street architect […] The lace-workers however did not call it Buckingham House but ‘Bobbin Castle’.”

A Guide to Old Wycombe High Street and Easton Street http://www.highwycombesociety.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/RaffetysChatsFinalVersion.pdf

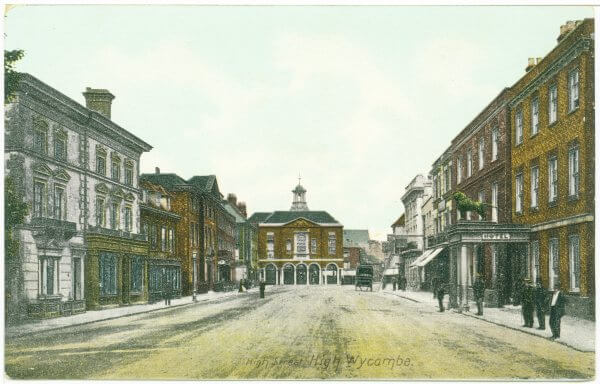

View of High Street, from east of the Red Lion towards the Guildhall, showing the Wheatsheaf and the Cross Keys, and on the left the location of the former premises of Thomas Gilbert, lace manufacturer, now (2006) WHSmith. (The large white building on the left is Buckingham House and Thomas Gilbert probably traded from the left-hand side of it) Courtesy of SWOP/Wycombe Museum

In 1841 Thomas Gilbert was living as an apprentice in the Hearn & Veary drapery shop in Easton Street, Wycombe with six others – Daniel Hearn was staying in the Cheapside, London branch. The lace men who lived on the premises in the 1840s were dealers who sold the materials to the lacemakers, bought the made lace and sold it on. The Hearn & Veary partnership was dissolved in 1847 – Joseph Veary retired, and Daniel Hearn continued to run the business. Thomas was his managing lace man.

Connections with grocers

There are many family and business connections found between individuals in the lace trade and grocers/drapers. The link may have been through the truck system – the lacemakers were paid partly in groceries. If the lacemakers lived in outlying areas, they may have had to go into the grocery shop once a week, say, so the transactions could all be done on the same trip. Also, these shops may have sold items like thread anyway, so it would be a natural extension to trade in the lace. An example of such a tradesman is George Hunt – apprenticed alongside Thomas Gilbert in 1841, he had set up as a draper in Thame by 1851 (probably with the bequest of £200 from Daniel Hearn’s will). In 1861 his wife’s aunt Hannah Britnell from Bledlow Ridge lived with them – she was a lace card maker (making the patterns that the lacemakers follow). There was also George Richardson of Bledlow – victualler, “Red Lion”, and grocer, draper, and lace dealer (Musson & Craven Directory, 1853) and William Ludgate of High Street, Princes Risborough – lace dealer and grocer (Pigot & Co’s Directory of Berks, Bucks, 1844). My own 3x great-grandmother, Jane Rogers, was a grocer in Askett in 1851 and 1861; her sisters who lived with her were lacemakers, and in 1871 she is described as a lace dealer.

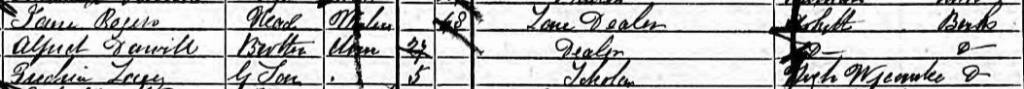

1871 census, Jane Rogers, Askett. Courtesy of Ancestry.co.uk

Jonathan Hearn, Daniel Hearn’s brother, was described as a hawker in the 1841 census and then as a lace dealer in 1851 when he lived with his daughter Jane and son-in-law James Lacey, a grocer in Easton Street, Wycombe.

Marriage and growth of lace business

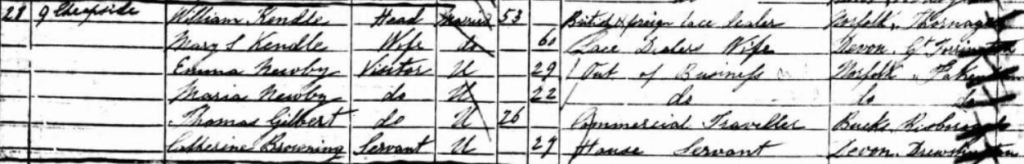

In the 1851 census, Thomas Gilbert was staying with the Kendle family at the London branch of Hearn’s business, as a commercial traveller. Interestingly, two other visitors staying there, Emma and Maria Newby, also had a lace connection – they were daughters of a Norfolk draper; Maria married Daniel Hearn’s managing grocer Frederick Goodeve and Emma married a London lace manufacturer.

1851 census: Household of William Kendle, Cheapside, a British and Foreign lace dealer, his wife, two visitors Emma and Maria Newby, Thomas Gilbert commercial traveller, and a servant. Courtesy of Ancestry.co.uk

Daniel Hearn died a few weeks after the 1851 census, and left generous bequests to his staff, including £20 and his organ to Thomas. Thomas presumably took over the business soon after Daniel’s death. In April 1852, aged 28, at St Vedast Foster Lane, in the City of London, Thomas Gilbert married 29-year-old Anne Matilda White of Wycombe – her father was a head collector of taxes, who lived at 4 London Road, Wycombe. Mr White was described as proprietor of a house and land and owner of woodland, so it would have probably been a good marriage for Thomas, who was described as a lace manufacturer of 9 Cheapside. He presumably moved back to Wycombe then; in 1853 he appears in local trade directories.“Gilbert Thomas and Co., grocers, tea dealers, provision merchants, linen and woollen drapers, silk mercers, hosiers, hatters, and lace manufacturers, High St.” (Musson & Craven Directory, 1853)

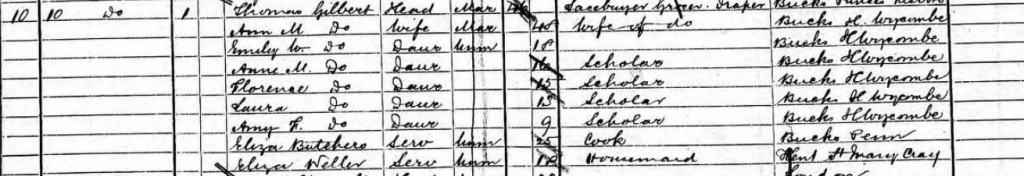

In 1861 Thomas and Anne with their growing family of five daughters (Emily, Anne Matilda, Amy Flora, Florence and Laura) lived in the High Street, at the shop; he was described as a lace manufacturer, grocer and draper, his live-in staff included three drapers, three grocers and a lace man, and he had a cook, a housemaid and a nursemaid – so he was reasonably prosperous. By 1871 Thomas and family had moved to 10 London Road (very close to Anne’s parents at 4 London Road) where they lived until 1902.

1871 census for Thomas Gilbert and family, 10 London Road, Wycombe – he was a lace buyer, grocer and draper living with his wife, 5 daughters, a cook and a housemaid. Courtesy of Ancestry.co.uk

Gilbert became involved in public life in the local community too – starting in 1860. He was a member of the town council 1860–1880 and was elected mayor in 1873; he was also borough magistrate, a director of both the building society and the waterworks company.

Peak and fall of Gilbert’s lace-dealing business

Thomas’ lace business became very successful. In 1862 he exhibited pillow lacegoods at the International Exhibition in London, on the Kensington site that now houses the Natural History and Science Museums. Also, that year, Thomas gave evidence to the Children’s Employment Commission, claiming that he was the most important lace manufacturer or buyer in southern Buckinghamshire and the adjoining strip of Oxfordshire. He claimed to employ – indirectly – about 3,000 persons. At that date he was about 37 years old.

“They are not absolutely engaged by me as workpeople, but I sell them the materials i.e. patterns, and silk or thread; and there is a mutual understanding, although no obligation, that I should take all lace for which I have sold the patterns, whether there be demand for it or not, and that the lacemakers should bring it to me and not to any other buyer.

For some I buy in their own villages […] [others] I do not deal directly with the lacemakers themselves but through the agency of small buyers, to whom I supply the materials and pattern […] these small buyers who have general shops, have a way of giving goods on credit for lace before it is bought. It is a bad plan but one that many adopt in villages.

The earnings of children are a great inducement to parents to put them to lace as soon as they can […] commonly at about 6 years old. Till the elder children reach this age [6] a family is only expense, but a mother with some of her little girls at lace may make nearly as much as the father.

[…] Machine lace is constantly pressing upon pillow lace, and the only means of keeping the latter manufacture alive is by constantly introducing new designs and kinds of lace as fast as the old are made on the machine.”

Rural life in the Chilterns was hard and the lacemakers’ wages were essential for keeping the family going. According to Dr S. D. Clippingdale, writing in Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine, ‘The Chiltern Hills and Dales in certain of their Natural and Medical Aspects’, (1909), some had an opium habit:

“A druggist […] stated that his firm, which had been established over a hundred years, formerly kept a box in which was stored crude opium for supply to the lace-makers. Another druggist stated […] that an old woman when out on Saturday night, making her purchases for the following week, would call regularly for her pint of laudanum. A local medical man stated that fifteen years ago it was common to observe the listless gait and the contracted pupil of the opium eater, and that patches of white poppy were still grown for making poppy tea for infants.”

More recently they might drink homemade wines – dandelion, cowslip and elderberry.

Truck system

Lacemakers were often paid via the truck system. This refers to a set of practices, under which truck wages or similar are used to exploit workers, their wages paid in specified shops which might have inflated prices. In 1872 Thomas Gilbert disputed with a correspondent in the South Bucks Standard:

“Correspondent: still grosser examples of ‘truck’ are to be found in connection with the lacework given out by ‘Liberals of Liberals’ and ‘Dissenters of Dissenters’ in the town of High or Chipping Wycombe. These tradesmen of the borough give out lace work at which good girl hands can make nominally six to ten shillings a week, in such a way that the poor creatures have to take more than sixty per cent, of their earnings from the shop, otherwise they cannot obtain the orders for the work.

TG: l am the tradesman who for a period of more than twenty years has almost exclusively given out lace work in this locality […]

Correcting […] your correspondent’s statement […] that the nominal earnings of good girl hands in lace work is from 6s. to 10s. per week, and putting it at its correct amount, viz., from 3s. to 7s. […]

[Daniel Hearn] did compel his hands to take out in goods about 60 per cent, of their earnings. But upon my representations and remonstrances he abandoned that vicious and unjust system and adopted cash payments for lace goods sometime before his death.

Correspondent: the extent to which they (the lace-workers) are thus chiselled may be learnt from the fact that most of them actually carry bits of lace to the country houses round and beg the ladies to buy, that they may obtain cash in return for their skill.

TG: Some few shuffling hands may do this, and the goods they offer, as a rule, are antiquated, out of date, frequently made of improper material and of bad workmanship. As to my hands doing this kind of thing, hawking their lace from door to door, why those who place themselves under my instruction would no more do this than would your correspondent make himself a night scavenger. They have in them far too much pride, and I will add proper pride too.

And in reply

Correspondent: I would deal as lightly as possible with the fact that Mr. Gilbert has, by his own admission, a share in a store. He denies that there is any truck in his dealings with the lace workers in connection with this store. But does he, or does he not, give facilities of credit at this store, and make the lacework stand against these petty accounts when it is delivered? Because if he does, then that is not, indeed, technically speaking, ‘truck’ but it comes to very much the same thing.” (London Evening Standard, Saturday 20 April 1872)

Fall and liquidation of the lace business

However, by the 1870s the handmade lace business in Buckinghamshire had been in difficulty for a long time because of machine-made competition, and finally it failed. The Education Acts of 1870 and 1880, which together introduced compulsory schooling up to the age of 10, and the Factory Act of 1878, which prohibited work before the age of 10, meant that children no longer had the time to make high quality lace. There was a move to beaded work and yak lace, but it was not sufficient to keep the lacemaking business profitable. Gilbert’s obituary states:

“The use of machinery at home, and the introduction of cheaper patterns from abroad, struck the death-blow to Buckinghamshire handmade lace, and although some revival of the trade took place when the Yak lace and beaded work came into fashion, it proved only the last flicker before the light went out altogether.” (Bucks Herald, Saturday 14 May 1904)

In 1876 his business went into liquidation. The ‘Dividends’ notice in the Bucks Herald in 1878 describes Gilbert as a pillow lace manufacturer, poulterer and cheesemonger of High Wycombe, Cheapside and St John’s Wood. (Thomas’ sister Frances and her husband ran a cheesemonger and poulterer shop at 10 Clifton Road, St John’s Wood, London with the help of her parents. It is unclear how and when Thomas became involved.)

“GILBERT, THOMAS (Liquidation), High Wycombe, Bucks, Cheapside and Clifton-road, St John’s Wood, both London, lace manufacturer, poulterer and cheesemonger. Final div of 5 ¾d., at Mr. J. D. Viney’s, 99, Cheapside, London, accountant.”

(Bucks Herald, Saturday 21 September 1878)

Thomas’ later life

After his business bankruptcy, Thomas continued living at Bedford House, 10 London Road, Wycombe for many years; in Kelly’s Directory 1899 he is still listed as a lace manufacturer at that address, and his obituaries state that he was involved in the rise of the beading industries, so possibly he started another business with his daughters.His wife Anne died 1900, leaving an estate worth £94. Thomas continued to judge lacework and beadwork in local exhibitions in Wycombe until 1901. In June 1902, the house at 10 London Road was sold at public auction – the South Bucks Standard reports it being sold by Miss Gilbert (despite Thomas still being alive) for £1,500. In 1911 his daughter Anne Gilbert was at 4 London Road, her maternal grandparents’ former home, and Thomas’ funeral notice lists him as living there too.

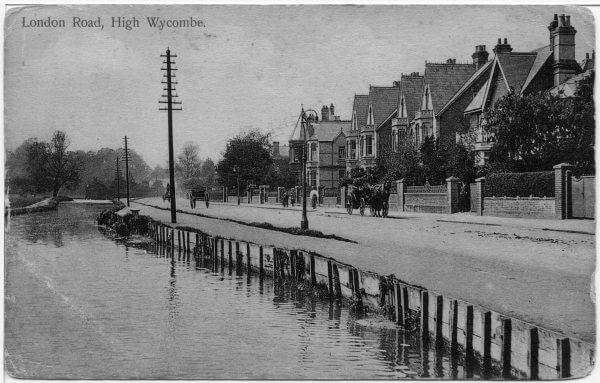

Looking west, a postcard view of the scene from the Rye along London Road, High Wycombe, November 1912. Copyright SWOP/High Wycombe Library. RHW:02034

Thomas and Anne Gilbert had five daughters, two of whom carried on the fancy bead and trimmings business in Wycombe, and one married a wealthy London lace manufacturer.

Emily (1853–1939) when widowed became a beaded lace manufacturer, then agent for bead and fancy trimmings.

Anne Matilda (1854–1941) was unmarried, initially a music teacher, then carried on a fancy trimmings business. In 1901 she lived at 4 London Road, her maternal grandparents’ house. She left £811 when she died in 1941.

Amy Flora (1861–1948) married Philip Vaile, wealthy lace manufacturer of 10 Ormonde Terrace, Regent’s Park, London. Two of their sons died in WW1. There are interesting similarities with Thomas Gilbert – Philip’s father Thomas Burdock Vaile was a commercial traveller in lace in 1851 and a lace manufacturer in Canon Street, London in the 1870s.

Florence (1855 – after 1911) married a gas works engineer and Laura (1857–1927) married a schoolmaster – both had no obvious connection with the lace/bead business.

It is not clear whether Emily and Anne carried on as lace, bead and trimmings agents using connections made from the Gilbert lace business, even though it had been liquidated, or whether they possibly acted as agents for their brother-in-law Philip Vaile.

Thomas Gilbert died in 1904 of a general decline and he seems not to have left a will. He appears from the glowing local obituaries to have been well respected.

“DEATH OF A NOTABLE MAYOR. By the demise of Mr. Thomas Gilbert, of High Wycombe, the county of Bucks has lost one of its most prominent personages. Mr. Gilbert, who was a member of the Town Council of High Wycombe from 1860 to 1880, was Mayor during an important period in the history of the town. He will be best remembered as one of the leading pioneers in his earlier years of the revival in the well-known Buckinghamshire lace industry and was also the originator of the cognate industry of beadwork, which has ever since found employment for hundreds of poor rural workers in the county.” (Bucks Herald, Friday 13 May 1904)

Another obituary in the South Bucks Standard, 13 May 1904 states:

“The obsequies were of the simplest character, and thoroughly in keeping with the unostentatious habits which characterised a long and useful life.”

The Bucks Herald, Saturday 14 May 1904, gives a fuller account of his life.

“Another link with Wycombe’s past has been snapped by the death Mr. Thomas Gilbert which occurred on Thursday night of last week at his residence the London-road, in the 80th year his age. The deceased gentleman was a native Princes Risborough, where he was born August 1824. When was about fourteen years of age he came to Wycombe an apprentice to Mr. Hearn, laceman, and afterwards succeeded to the business, which became a very extensive and lucrative one.

In fact, Mr. Gilbert was the last to carry to any extent the lace trade, which had flourished Wycombe for centuries, and with glove-making and the manufacture of paper had been the principal staple industry of the town, long before chairmaking was even dreamed of. The use of machinery at home in lace-making, and the introduction of cheap patterns from abroad, struck the death-blow to Buckinghamshire hand-made lace, and although some revival of the trade took place when the Yak lace and beaded work came into fashion, it proved only the last flicker before the light went out altogether.

Mr. Gilbert, although always a very busy man, found time to devote to public duties, and for many years was a prominent and useful member of the Town Council. In 1873 he was elected Mayor, and during his term of office an attempt was made to extend the Borough boundaries, which failed, and to open up Castle-street as approach to the railway station, which succeeded. In politics Mr. Gilbert was a Liberal and a Free Trader, and you could not be in his company long before he introduced some quotation or remark of Richard Cobden.

When the Home Rule split occurred, he became a Unionist. Although he had not been in the Town Council during the last seven years he continued to evince the liveliest interest in the proceedings of the Corporation, and it was only about three weeks ago that I had a chat with him upon municipal affairs. His last illness was not caused by any specific complaint, but arose simply from loss of vital force. The funeral took place on Wednesday amid evident signs of sympathy and regret.”

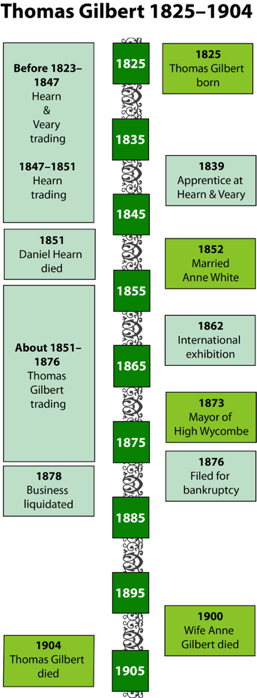

Timeline prepared by Woodlanders’ volunteer Rebecca Gurney

Want to get involved?

If you’ve been inspired by this account, gathered by our volunteers, you can learn more about our Woodlanders’ Lives and Landscapes project. You can also contact the project lead- Dr Helena Chance– to learn more about volunteering.

Related news

Grazing livestock in the Chilterns

With spring comes longer days, warmer weather and livestock grazing on lush spring grass.

Chilterns New Shoots: applications now open!

Applications are now open for the 2024/25 cohort of Chilterns New Shoots – a wildlife and conservation programme for 14-18 year-olds.

Bluebells: the sign of spring in the Chilterns

Bluebells flower in abundance in ancient woodland in early spring and are found throughout the Chilterns.